The first four lessons of my Holocaust scheme of work/learning – all began with a shoe, a child’s toy and by introducing an ‘Authentic encounter’ approach to learning

I began my scheme asking ‘How can we use ordinary things to develop our historical knowledge and understanding?’ The lesson one objective was to discuss in small groups and class, the possible history of an artefact – in this case a shoe. I wanted to encourage students to question the artefact as individuals and to search for a deeper layer of meaning, asking how it is we know what we know, exploring inference, hypothesis and evidence. Student engagement with ‘Ordinary things’, across all Year 9 groups, was fantastic and the skills they honed were fundamental to history and their becoming ‘better historians’. The lesson sought to develop students source analysis, so this was demonstrated in the student’s outcome; the completion of the ‘mining the evidence’ triangle and answering the question ‘What can ordinary objects tell us/how can ordinary objects develop our understanding?’

I began my scheme asking ‘How can we use ordinary things to develop our historical knowledge and understanding?’ The lesson one objective was to discuss in small groups and class, the possible history of an artefact – in this case a shoe. I wanted to encourage students to question the artefact as individuals and to search for a deeper layer of meaning, asking how it is we know what we know, exploring inference, hypothesis and evidence. Student engagement with ‘Ordinary things’, across all Year 9 groups, was fantastic and the skills they honed were fundamental to history and their becoming ‘better historians’. The lesson sought to develop students source analysis, so this was demonstrated in the student’s outcome; the completion of the ‘mining the evidence’ triangle and answering the question ‘What can ordinary objects tell us/how can ordinary objects develop our understanding?’

There was a real sense of ‘curiosity’ and discussions which were firmly focused on the object. Questions were of a much higher quality and left students ‘wanting to know more’. I used the video to narrate the context; I have never seen my Year 9s listen so closely! This was a brilliant start to the UCL lessons; students felt it set up the scheme and, personally and professionally, teaching this first lesson really made me look forward to teaching the rest. I was excited and inspired to see what learning would follow.

Building up the first, lesson two drew upon the Centre’s ‘Authentic Encounters’, it asked students to reflect upon how can an original artefact enrich understanding of the Holocaust. The objective here was for students to question their own understanding and search for their own meaning of the past. Based on last lesson, students came in to the classroom much more engaged and excited; they weren’t disruptive at all, but there was a real shift in their enthusiasm. I had put the image of Barney’s truck on the board as they came in, so source analysis started on entry. This is something that I do more regularly now, it’s become a strategy to be relied upon, as this means there’s an image to look at a ‘hook’. I normally have a ‘self-starter’, but these images promote student inquisitiveness much more effectively than ‘what’s in the box?’ or ‘guess the mystery object?’, which imply that there is a correct answer. This approach is open-ended; there’s a perpetual sense of ‘not quite knowing’ which isn’t revealed until the contextual narrative, which comes after the source investigation and questions; many of which I have left unanswered. I wanted to come back to the questions with students later, to see if they can answer them with their own knowledge – so this provided ongoing assessment for learning – and gave students a clear sense of their own progression, particularly in the disciplinary skill of source analysis.

The outcome for this lesson was familiar to the first – Completing a the ‘mining the evidence’ diagram, but also a photo analysis sheet that enabled us to explore source evidence and model how to ‘read an image’.

The outcome for this lesson was familiar to the first – Completing a the ‘mining the evidence’ diagram, but also a photo analysis sheet that enabled us to explore source evidence and model how to ‘read an image’.

The homework that supported this lesson allowed students to search for their own artefact from the Holocaust, with a starting point of Yad Vashem. There were a huge range of artefacts chosen and choices were well-supported with explanation, description and labelling.

By lesson three I wanted students to consider who European Jewry, pre-1939, were. In order to explore ‘what was lost’ and tackle significance of the Holocaust, it would be essential to reflect upon the vibrancy, diversity and history of the people most impact – the Jews. I have been especially taken by the results of the UCL student research in this regard and also moved and inspired by the Beacon School study visit to Poland. My scheme of learning reflected for example some of the places, Jadow and others, from the trip that so revealed ‘the Void’ to me. I wanted to help my students explore this in the classroom, so by devoting time to this, I aimed to enable students the time, space and opportunity to reflect upon ‘the Void’ and be better able to recognise and counter stereotypes and myths about Jewry.

The students completed ‘Busy Bee’ frameworks by mining and exploring a range of evidence and sources – including painting, case studies, maps and card sort, to provide a multi-faceted answer to the question ‘Who were the European Jewry before WW2?’ Whilst a creative lesson – they were throughout honing their understanding of cause and consequence.

Students enjoyed engaging with the paintings from the Ben Uri gallery. They took a lot of prompting to answer questions about the paintings and needed a lot of guidance. However, this is still early days with this type of analysis in History lessons. It’s something I am continuing to build on, if not differentiate then scaffold better for next year. If I am honest, I then wasn’t sure if students would be able to do the Centre’s card-sorting activity (Who were the six million?). I was wrong. I should expect much more from my students. And have more faith in my ability to explain something well! The maps were really interesting; it meant a great link to geography was made. The students were so into the card sorting activity that I should have allowed more time and perhaps extended this in to two lessons; the writing down in the Busy Bee took longer – I wonder if I need to do this next year? I am wondering if there’s another way of showing their understanding? Either way, I think two lessons might also allow them to explore more specific communities and perhaps some case studies of people and their way of life. Of course, time is always precious – but I feel this would be a powerful, meaningful addition if possible.

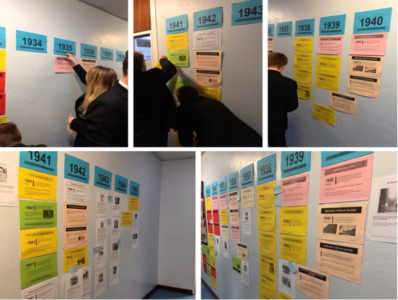

So, with the above as our foundation, we could then ask ‘What was the Holocaust’ in our fourth lesson. Using the Centre’s interactive Timeline materials, my objectives were manifold. I wanted students to begin to understand some of the different experiences of victims of the Nazi regime, that there were different programmes of persecution and mass murder. In keeping with the research briefings (1+2), I felt it important students were able to recognise the differences and similarities between all of the persecuted/murdered groups and begin to appreciate the scale and complexities of the Holocaust. All the while, the definition of the Holocaust would be hinge – what was it, and what was it not? To what extent did my planning, the teaching and learning achieve the desired outcome of developing my students as historians, honing their interpretations and representations, source analysis, change and continuity and significance.

This activity spanned two lessons and I taught this in a different order to that suggested in the Centre’s Lesson Plan. Our students have very limited understanding of the context of the Holocaust (other than what they bring with them to the lesson, which may have come from a plethora of sources), so I chose to do the dates and events first. I then followed this with the Case Studies, so students had a background knowledge of the context in which these people/groups were placed. Overall, students embraced and engaged with this activity. I put the Timeline out in the corridor, although my corridor only allows for half of it to go on each side. Had I used the full length of the corridor, I would have impinged upon the Geography space and potentially disrupted the lesson there as well. My decision to split the timeline into 1933-1940 on one side and then 1941-1945 on the other, worked in my favour. Students physically saw the ‘turning point’ in the timeline and had to turn 180 degrees to look at the other half. I didn’t have the space to do this in my own room, although maybe next year, I’ll try and see if this makes any difference to the activity. My Y10 and 2 classes of Y8 students fully engaged in this activity. They were totally on task and really enjoyed the different learning space. However, my third (lower ability) class struggled in the minority to engage (only a couple of times) – I did wonder whether the change was too much? Those who would normally find a classroom situation difficult found this very difficult to concentrate upon; they veered towards the edges and participated when directly questioned, although this is more of a classroom management strategy to consider for next year. Should I break the task down even more? Should we keep returning to the classroom (familiar environment) more often? Could there be some questions for students to answer and then go out to the timeline again? Or could this simply be solved by doing the activity within the ‘safety’ of the classroom? Overall, the activity was a huge success. Students worked really well together as a whole class to construct the timeline – no mean feat when there are 30 of them!

For the second part of the activity, students worked together again to return to the timeline once they had read the Case Studies. For the duration of about a week, the Timeline stayed out in the corridor. What was particularly interesting was the amount of students and staff who stopped to read it. Really study it. Some of the cleaning staff came down to look at it, because one had spoken to the other and said they should come and have a look. It was great to have the opportunity to speak to anyone who stopped to read it and engage in discussions with them – Y7 were particularly interested and were very keen to talk to me about particular events. Learning was happening in the corridor and students/staff were asking questions about the material. Interestingly, the cards which caused the most interest were ones about how different groups were persecuted.

The last part of the activity was mostly held in the classroom and involved students creating an argument as an extended piece of writing against one of the ‘Myths’. I encouraged students to go out in to the corridor to take photos of the case studies and corresponding events to help them in this task – they really enjoyed this and were very mature about this. All this learning resulted in students writing an article for the ‘Mythbuster Weekly’, choosing one of the headlines to provide a supported argument to the myth conveyed in the headline.

The last part of the activity was mostly held in the classroom and involved students creating an argument as an extended piece of writing against one of the ‘Myths’. I encouraged students to go out in to the corridor to take photos of the case studies and corresponding events to help them in this task – they really enjoyed this and were very mature about this. All this learning resulted in students writing an article for the ‘Mythbuster Weekly’, choosing one of the headlines to provide a supported argument to the myth conveyed in the headline.

By Charlotte Lane, Torpoint