Credit © Barbara Winton

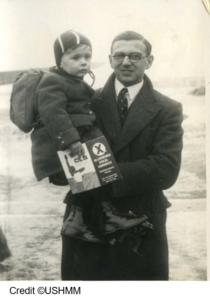

When we are faced with difficult issues today such as the growing hatred and aggression by some groups against others who are different to them, it may seem impossible as an individual to stand against this tide and make any impact to resist it. The ongoing refugee crisis across the world seems another intractable problem and arguments rage over how to react. However compassionate and concerned we feel, it may seem that there is nothing we can do to make any difference. I believe that my father’s work 80 years ago, instigating a Kindertransport, bringing endangered, mostly-Jewish children. from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia to safety in the UK, could set an example of a positive way to respond.

In 1939 the challenge Nicholas Winton made in a newspaper article to the British public to ‘stand together’ with those vulnerable children in Europe was this:

Should we “go home resolved to live good lives” or should we in fact decide to “give one’s time and energy in the alleviation of pain and suffering”? The former he called ‘passive goodness’ and the latter ‘active goodness’. He believed that taking action to help those in need was the right way to live a meaningful and moral life. With the ever- increasing threat of discrimination, violence and imprisonment towards Jewish families in Europe, he knew sympathy alone was not an acceptable response.

Together with other like-minded colleagues who volunteered in this endeavour, they worked feverishly to deliver those children at risk to safe homes in the UK. Alongside Trevor Chadwick, Doreen Warriner and others who were appalled at the hatred and violence shown to Jews and other minorities by the Nazis, they brought to safety nearly 700 Czech and Slovak children. At the same time larger organisations transported nearly 10,000 children from Germany and Austria.

Together with other like-minded colleagues who volunteered in this endeavour, they worked feverishly to deliver those children at risk to safe homes in the UK. Alongside Trevor Chadwick, Doreen Warriner and others who were appalled at the hatred and violence shown to Jews and other minorities by the Nazis, they brought to safety nearly 700 Czech and Slovak children. At the same time larger organisations transported nearly 10,000 children from Germany and Austria.

The British public responded to his challenge and many hundreds of families offered homes to the children, fostering them through the long years of war. Many continued to care for their foster child once it was discovered, at war’s end, that their stranded families had been murdered during the Holocaust. People did what they could: some offering homes, some fundraising for the £50 repatriation guarantee the government required for each child, some volunteering in small local groups or larger organisations to do the vital work to get the children to safety. All played their part in saving lives and making futures for those children.

In 1939 many people stood together with those in need and stepped forward to do something positive to help. They knew compassion was not enough, action was needed. At the time those who helped just thought it was the right thing to do – to give sanctuary to those in need. They did not know what the future would bring if they didn’t help, that they were saving those children from cold-blooded murder. 80 years on, we can look back and recognise the absolute importance of what was achieved. By that endeavour, 10,000 lives were saved and those child refugees went on to enjoy successful, productive lives, contributing socially and economically to their host communities and new country.

Today, when the reaction to refugees in desperate need of sanctuary is in many cases to demonize, it is vital to educate young people, as well as the general public, about this history and the universal human values of compassion, tolerance, respect and dignity for all people that underpinned the Kindertransport and other rescue initiatives. But it is also vital to recognise that supporting those values needs to lead to positive action if it is to have real effect. By learning the lesson from the Kindertransport and becoming active in our local communities or further afield, standing together with those in need, much can be achieved.

That is why the UCL Centre’s for Holocaust Education’s work is so important; they ‘stand together’ with schools and with teachers in their day to day work. I welcome that my father’s story is incorporated in that work, including their ‘British Responses to the Holocaust’ lesson materials. These programmes encourage asking questions about the stories we choose to tell ourselves and the relationship of the past to the present. What more could have been done then, what should we as concerned citizens be doing now?

I hope the Centre will continue in its mission to support the teaching of this highly complex and difficult subject. We live in challenging, divided and difficult times. My father‘s motto was ‘if something is not impossible, there must be a way of doing it’. If remembrance and learning leads to action to help build a kinder, safer, more compassionate world, then that would truly honour his memory. The Centre’s work, along with other organisations like the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, is providing a powerful mechanism for standing together, offering support and effective change. As my father said, “Don’t be content in your life just to do no wrong, be prepared every day to try and do some good.”