To study the history of Bergen-Belsen is to encounter paradoxes – narratives and perspectives that can challenge doxa and common beliefs about the camp, the Holocaust and Liberation.

One common belief arises from the shocking images that the British Army Film and Photographic Unit captured in Bergen-Belsen in the days following liberation on thirty-three rolls of film and 200 photographs. These images – such as those showing Private Frank Chapman bulldozing bodies into mass graves in April 1945 – have become grimly iconic and have come to define understandings of the site we call ‘Bergen-Belsen.’ They often come to stand also, by proxy, for concentration camps in general.

As Nick Waschmann has argued, the problem is that ‘concentration camps… are often seen through the lens of the liberators’ – lenses which capture the situation at liberation only, not what went before (Wachsmann, 2016, pp. 3–4). Iconic liberation images are, in many ways, atypical of the camp in the three years of its history and represent mostly its final stages as a ‘horror camp’, from December 1944 when Josef Kramer was transferred to Bergen-Belsen as commandant with cohorts of guards from Auschwitz. This was when ‘standard’ SS discipline (including the use of ‘kapos’) was imposed on the camp as a whole. Conditions at Bergen-Belsen had been deteriorating since August 1944, however, it was from Kramer’s arrival that Bergen-Belsen truly could be called a ‘horror camp’ in which tens of thousands of inmates were deliberately done to death through systematic cruelty, neglect and starvation. This process accelerated exponentially up to April 1945, as transport after transport of prisoners were transferred to Bergen-Belsen from Buchenwald, Dora Mittelbau, Auschwitz, Dachau, and other elements of the SS camp network as the Nazi ‘Reich’ shrank and finally collapsed.

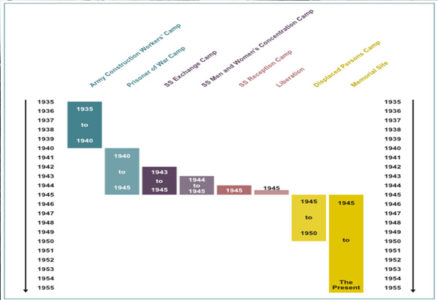

When it was founded, Bergen-Belsen had been intended as something very different – something equally inhumane, but in senses other than those that usually come to mind when one hears the name. When the camp was created – on the site of a former army construction camp (1935-40) and Stalag XIC, a prisoner of war camp, (1940-1943) – it was as a ‘Detention Camp’ (neither an ‘internment camp’ nor a standard SS Concentration Camp) and it was something of an anomaly.

The concentration camp universe that the Nazis created in Germany from 1933 was a monument to barbarism and a stain on the record of human history in the twentieth century and beyond. It was also, however, a highly differentiated ‘universe’ and one that is widely misrepresented in education and in popular culture, where parts – Bergen-Belsen or Auschwitz Birkenau – are often taken to stand for the whole. Death was common in most concentration camps, but few concentration camps were ‘death camps’ – sites devoted to killing operations and equipped with mass murder facilities such as gas chambers. Death camps – Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor and Treblinka – do not figure widely in popular culture in the way that camp complexes like Auschwitz I-III and, to a lesser extent, Bergen-Belsen, do. Even the Auschwitz complex – where over a million people were done to death mainly by gassing – is widely misunderstood: it was not exclusively a ‘death’ camp but was also a vast complex of slave labour camps and factories.

Bergen-Belsen stands out in the concentration camp universe, almost exclusively, as being a camp in which it was intended – in the words of Heinrich Himmler when the camp was founded – that Jews should not work and should ‘be kept healthy and alive’ (Shephard, 2005, p. 12). It was also unique in being the only camp intended exclusively for Jewish inmates within the borders of the pre-war German Reich. The other camps to which Jews were transported for immediate murder or murderous slave labour were in newly acquired territories ‘in the East’. Bergen-Belsen, by contrast, was in the heart of Germany, near the town of Celle on Lüneburg Heath, adjacent to German Army training barracks.

Bergen-Belsen was founded as an ‘exchange’ camp with the intention of isolating prominent or ‘foreign’ Jews – such as the 350 Sephardi Jews with Spanish, Turkish, Argentinian and Portuguese passports who were deported to Bergen-Belsen from Salonika in July 1943 – so that they could be ‘exchanged’ with Germany’s wartime enemies for German prisoners of war, war materials, and so on.

The fact of ‘exchange’ is paradoxical – that there should have been a camp designed to keep Jews alive so that they could be ‘exchanged’ to freedom runs counter to our narrative expectations about the Holocaust, which was, of course, an attempted genocide of all the Jews of Europe. Despite this, however, exchange confirms expectations about Nazi barbarism. What better illustration could there be of Nazi racism and dehumanization than their treatment of 2,500 Polish Jews deported to Bergen-Belsen in April 1943. Following a period in which the Nazis evaluated the ‘exchange’ potential of their papers, 1,800 of these inmates, deemed to have forged or low-value papers, were deported ‘East’ in early 1944. These Jews, who would have had knowledge of how the Nazis treated Jews in the East, lived for three quarters of a year with the false hope of ‘exchange’ before the Nazis transported them to their deaths. ‘Exchange’ also gives a window into the delusional ideology of Nazism that underlay all aspects of the Holocaust. The premise of ‘exchange’ was the assumed existence of ‘World Jewry’, pulling the puppet strings of governments in the United States, the Soviet Union and elsewhere. The fact that so few Jews were in fact ‘exchanged’ underlines the fantastical nature of that ideology.

As well as giving us insights into the Holocaust and its perpetration, the stories of the site at Bergen-Belsen can give us insights into the wider history of German brutality during World War II, challenging widely held doxa and common beliefs. For years – and particularly once the development of the Cold War made West Germany a valuable ally – the brutalities that were perpetrated against Germany’s enemies during World War II were attributed exclusively to the SS in an intellectual operation that allowed the ‘contagion’ of Nazism to be sequestered and kept at a distance from the German state more generally. What happened at Stalag XIC – and the wider complex of prisoner of war camps around it – points to the falsity of that narrative. Before it became Bergen-Belsen Detention Camp, the site had been a prisoner of war camp where Soviet prisoners were systematically mistreated, neglected and starved to death by the German Army. It is estimated that more than 30,000 Soviet POWs were starved and worked to death in the camps on Lüneburg Heath in 1941 and 1942. At least 14,000 of the 21,000 Soviet POWs who were sent to Stalag XIC were done to death by the German Army and buried there before any thought had been given to the idea of developing an ‘exchange’ camp on the site.

The history of the site at Bergen-Belsen also reveals a great deal that is often forgotten about the aftermath of the Second World War and the end of the Holocaust. It is often assumed that 1945 brought ‘liberation’ for the victims of Nazism. This is, of course, naïve: you cannot easily be liberated from life-changing experiences of torture, slave labour and genocide, whose consequences lived-on for victims and, often, affected the experiences of their families and the next generation.

There is another sense in which the history of Bergen-Belsen can have a somewhat destabilizing effect on the doxa or common beliefs about liberation. There can be no doubting the heroic nature and scale of the rescue operation that the British Army and numerous voluntary organizations completed in the former concentration camp and adjacent army barracks between April and June 1945. There can be no avoiding the fact, however, that there were still 12 thousand Jews in Bergen-Höhne Displaced Persons camp after liberation and that many remained there until 1950 when the DP camp was finally wound-up.

A paradox relating to the experience of many Jewish victims of the Holocaust in Bergen-Belsen and elsewhere is captured in the words of Josef Podemski, an inmate of the DP camp who emigrated to Israel in 1949 and then to Canada. He was interviewed by researchers at the Bergen-Belsen Memorial in 2000 and said: ‘‘We’re not Hungarian, we’re not Czech, we’re not Austrian. We are Jews! This is what Hitler made of us!’ (Buchholz, p.362). Many Jewish former citizens of Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and other Eastern European countries who the British and their Allies categorized as ‘displaced’ persons refused to be ‘re-placed’ to their countries of pre-war residence and citizenship. For many, there was nothing to return to – as families and entire cultures had been wiped out in the Holocaust, and, in many cases, as there was a perception that they would not be welcomed back where the local population had collaborated in their persecution or profited from their absence. These ‘Displaced Persons’ often now understood their ‘place’ to be in Israel at a point at which it suited British political interests to prevent most of them from going there, a situation that only changed after the State of Israel was founded in 1948.

Note

These reflections draw on the research contained in Bergen-Belsen: A Brief History for Teachers accessible on the Belsen 75 web page (https://www.belsen75.org.uk/school-resources/).

References

Buchholz, M. (Ed.). (2010). Bergen-Belsen—Wehrmacht POW Camp, 19401945, Concentration Camp, 1943-1945, Displaced Persons Camp, 1945-1950: Catalogue accompanying the permanent exhibition. Lower Saxony Memorials Foundation / Wallstein Verlag.

Shephard, B. (2005). After Daybreak: The liberation of Belsen, 1945. Jonathan Cape.

Wachsmann, N. (2016). KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. Abacus.